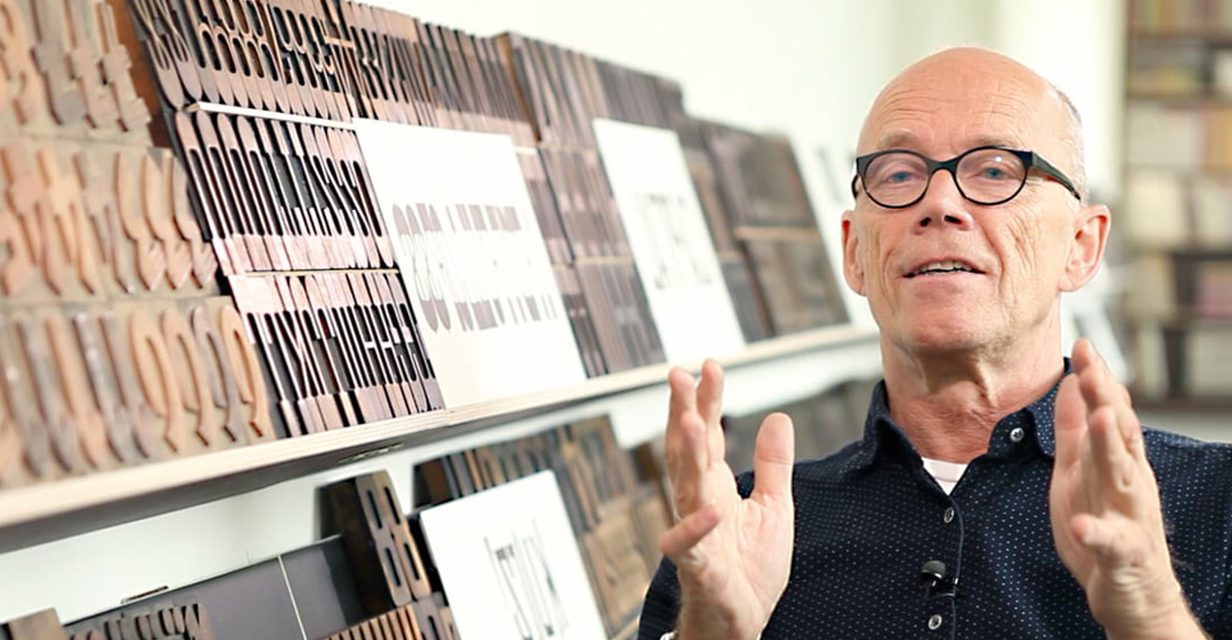

Here, we are in conversation with Erik Spiekermann, one of the leading graphic designers and typographers in the world. His original claim to fame was designing all the sign and type face for the Berlin underground rail system but he has founded several companies and influenced designers and design thinking well beyond the borders of Berlin. He has designed several different fonts that are widely used, the most famous of which is FF Meta. His first company was called Meta Design, which he founded in 1979 and later went on to create his own brand of fonts called FontFont. The man loves print and the process of creating fonts and using a printing press. When he was 12, Spikermann’s father gave him his first box of type. That’s where his love for type began and it continues to today. Today, Spikermann calls Berlin, London and San Francisco his home. We spoke with him when he was in San Francisco. Here, he shares what he believes were some of the earliest talents he discovered himself to have.

Below is a transcription of the Design In Mind interview with Erik Spiekermann.

Spiekermann:

I noticed very early on that I was very good, and I can’t remember when that happened, but that I was pretty good at convincing or talking people into doing something with me because I have enthusiasm. I seem to have more energy than some people and I have loads of ideas, which I never think to the end. I just start things and then I quickly lose interest or I realize, “oh my God this is getting detailed, this is gonna demand looking at spreadsheets,” which I don’t do, so let’s get in some people who can do this really well. And I have no problem whatsoever hiring people or working with people who are really, really good at something, better than me, because I am good at something also. And then I found out that maybe after doing it for twenty years, that that was actually my secret. I was not afraid of hiring above me. Most people are, especially when you are starting a company you get this, they keep hiring below them and after ten years everybody is kind of half monkeys in there because they keep hiring below.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And if you have four or five hierarchies in the company, in the end you just have all sorts of yes people who don’t wanna lose their jobs but they don’t do anything. And I have always benefitted from having people around me who were difficult but ironically or not ironically, surprisingly or most pleasantly, I know most of them still, so we’ve kept in touch, we are still friends. I have this network of about, somebody worked it out, it was a spread in I-Magazine six or seven years ago, when they went to Berlin, they were gonna write about Berlin and John, the editor, wrote to me and said, “I have been here for three days and everybody has worked with you”.

Arkitektura:

Yes, I read that.

Spiekermann:

They did that big plan. And it was like six hundred people that have their own business now that worked with me at one time or were at least my students. And of course if you look at over what, forty years of working professionally, that is not surprising, because I had a company with two hundred people. Now we have like sixty, seventy, eighty people whatever. So obviously I have touched a lot people and I don’t remember every one of them but I remember most of them. And I am actually interested in people, I actually like people. I don’t have to go around and pretend I am interested in how the dog is doing, I actually want to know, I am curious.

Arkitektura:

You’ve always been that way? Even as a kid?

Spiekermann:

I have always been. My mother always complained that I was…I think in the forward for that book that you were talking about that was written about me but not by me, I say myself that I am a blabber… My son translated it into English, he does translations.

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

He said blabbermouth.

Arkitektura:

Yeah.

Spiekermann:

I can only think when I speak, so I speak a lot more than most people because as I speak, I talk to myself.

Arkitektura:

And how is that for your wife?

Spiekermann:

We have that little in/out thing. [In one ear, out the other.]

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

And, of course, unfortunately, back home, with a wife, you don’t speak that much because you have basically been through it all, you know what I mean? You’ve covered all the bases, you have been through all the topics. But I know when I am with people, especially new people, I tend to always shock them at first because I give them pretty much everything I know for the first twenty minutes.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And if they survive that then they realize, “ok”. And I used to do a lot of radio interviews in the eighties. When I lived in London, I worked for a German radio station. I did one Saturday noon program where I was just sending tapes and they would mix them and my interview method was always I would literally talk to people for like ten minutes and they would, “aahuhuhu” you know, they couldn’t get a word in but then I would stop and then were so full of stuff that they wanted to say then they would talk for half an hour.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

Now, I won’t have to interrupt them anymore. Because I made them feel relaxed.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And, again, I didn’t realize that was my method. Just something I did and then after a while I thought…And of course the guys, the producer said, “how come you get these people to talk so much?” and I said because you cut this off the tape, I talk to them a lot first and that opens them up somehow.

Arkitektura:

Well, it goes to show you how that talent is great for a business person. I mean that is your key to success, your ability to bring people together, to be charming for lack of a better word. To be personable.

Spiekermann:

Well, it is not always successful with the clients because clients, especially once you get to larger corporations and I think especially over here in the States, people tend to be a little more formal and want to have those hierarchies intact. And as a Designer you kind of don’t fit in anywhere. So when I had few hundred people working for me, I was the CEO, so in a away I was on the CEO level but if you are a CEO of around two hundred thousand people, I am not on the same level. I am still a service person, I am like the cleaning guy. You call in the Designers and they wipe the problems away with their design stuff and then you send them away again. So you are never quite at eye level. I am little bit more now simply because I am older than most of my clients and they tend to listen because, again, that is the authority thing, especially in Germany. You know if you are Professor/Doctor like I am and you are old enough then they would…they may not necessarily believe everything you say but they have to because you are whatever, this old guy.

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

But my method of just storming into people and saying it how I see it has not always been very popular and I have often had my colleagues who were with me totally shocked and going out afterwards saying, “oh my God, I can’t believe what you told this guy”. And I now I know I have this, you know, the famous “don’t work for asshole” rule, both with nor for. And it’s worked out well, now I have realized that I’ve always had this gut feeling, “this is not gonna be good.”

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

These guys aren’t really interested; they have some money to spend, they don’t care who we are, they don’t really wanna open up, they don’t really wanna solve any problems, they just have money to spend. We just happen to be in the vicinity and I feel that now, it is like a relationship. You may be, can I say this on air? Horny. You go out and you are like, if you are younger and you go out, and you are looking for a date, you know what I mean! You make that mistake when you are younger and then you wake up the next morning, you think, “what have I done?”

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And that is a mistake I don’t make anymore. I am talking about clients now.

Arkitektura:

I understand.

Spiekermann:

That you are so blinded by your own testosterone or by the desire or by the need to get money to get jobs for your guys back in the office that you forget all the warning signs you think, “ok, I need this work, these clients, they might be assholes, it’s not gonna be a good relationship, we won’t be valued but we need the turnover.”

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And I don’t do that anymore. Like we stopped doing pitches, certainly unpaid even paid pitches. We need a relationship with our clients and you know what?! It served us pretty well because nowadays they call and say, “we hear you don’t do pitches,” and I say, “damn well we don’t do pitches,” and they say, “well, what do you do instead?” So if you stick by your guns, it does pay off, it just takes a while.

Arkitektura:

If a young Designer were to say “what’s a warning sign? What would that warning sign look like?

Spiekermann:

Well for example if a client, and we had this recently, some fairly large project, a promising project. First of all they ask twenty design studios of totally different backgrounds, very small, very large, to submit their portfolio. Now that’s already a warning sign. Twenty people! Like, couldn’t you hold, you know, get a little closer to find out a little more but that’s just throwing out the net, not giving you the work. And then they invited five of those people for a, “make us some ideas”. Like do free work.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

You know, compose a free bloody Opera and then we will decide whether we gonna put it on show and I said, “no bloody way,” and of course it turns out then that we didn’t take part, four or five other people took part. Of course they didn’t decide for one of them, they said “hum,hm,haa,hum” what they gonna do is go on back home and get somebody’s sister or brother or whatever and make their own shit out of it or because they didn’t bother to sit on it and decide what they really wanted and needed. They thought they give this away to somebody else. And I don’t like this. Clients, when they have a communication problem, which is what we do, we solve communication problems, we design whatever is needed to solve that problem, they need to sit down and think what is their real issue. And if they can’t do it on their own we are very happy to help with that. And it is almost like being on the couch with your shrink. You bring out the problem and as you speak about it, you realize they might want a brochure but maybe their products suck in the first place or whatever or they are looking at the wrong market, whatever it is. And we are good at finding this out and then we decide what strategy, what media, we use for it. But if they really are not prepared to speak…It is like going to the doctor and not being prepared to speak about your sickness.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

That’s not gonna work. You gotta open up and admit that you can’t sleep at night, you have to go to the toilet too often or whatever it is and to doctors we open up because they have that status. But in a way we are the sort of cooperate doctors there. If a client won’t open up to me then I know it is not gonna work. It’s only been the last three or four years that I’ve started thinking about what I am doing. I’ve always just done it. I am not the one that is to step back and develop this theory. I finally forced myself I don’t know five or six years ago to run a manifesto for our company when we started regrouping and I brought in new partners. Seven years ago, I told my partners that I was gonna leave in seven years time which was last summer because I am officially retired now. Then I had to get some perspective and sort of leave a few things as markers but before, I just did it, I never had a method. It would be too arrogant to say that I planned all this, that I knew what I was doing. I just did it and I was lucky. Obviously, I have some talents that work and I was also lucky to be with the right people in the right place at the right time. We did the job that put us on the map. Basically, it was 1990 when we did the signage for Berlin transportation or Berlin transit because the wall had just come down.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

You know what, if that hadn’t happened we would have never gotten that job. And that happened to have happened and had nothing to do with us. We happened to be in Berlin and happened to know the people and we were the only people that could do the project in the first place and that pretty much put me on the map in Germany as sort of Information Designer. And that was sheer luck.

Arkitektura:

When I was interviewing Tom Dixon who is a Designer…

Spiekermann:

I know Tom Dixon.

Arkitektura:

…last summer, it also was this kind of sheer luck of his career, I mean there was no real trajectory. One thing lead to another.

Spiekermann:

Yes. Well, as I would never use the word career, as it is such an American word. Career always sounds like you were planning this, you have to go to University then you do this for five years, you do this for five years. I have never had a resume, I have hardly got a bio which people always want from me and it embarrasses me to write it.

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

I haven’t got a resume, I don’t have a website where I show off all my fantastic projects or our fantastic projects and I certainly don’t read my Wikipedia entries. And when I do it annoys me how wrong they are but that is life. Career would imply some sort of plan. I never had a plan. I just do stuff, things have happened. I never finished my degree at the University, I did all sorts of things, I have learned few trades but I never did the exam. I always got bored too quickly.

Arkitektura: Well, I mean I think you didn’t finish your degree at University from what I read because you had a child at such a young age and you had to work.

Spiekermann:

I think that is probably post-rationalizing. Yes, I could have still done it, yes of course. I remember going to University and I was only, what, twenty and it was interesting but it wasn’t as interesting as I hoped it would have been. There was just too much bureaucracy, there were too many people who weren’t interested, some of the professors weren’t interested either, I was unlucky there. I had people at Art because I started doing history of Art and then went into Architectural history. I thought it was gonna be way more exciting than it was, I thought, “my God, they are gonna teach me how to look at the world and to find some sort of instruments: how do I judge beauty? How do I judge what a good painting is? And all they were giving me is stuff I could have easily gotten from any old book. So I was very, very disappointed at University. And that is why having my son when I was twenty one and I had just been to University for a half a year by that time. I still went every now and again but I wasn’t in it. Other people also work, other people also have children and still finish their degrees, I just wasn’t interested.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

So it was a nice excuse in a way, I think.

Arkitektura:

And maybe the reason why you don’t distinguish the career thing is, I mean, I understand it is an American thing but it sounds like, you know, your life and your work are just so intertwined. There is no distinction.

Spiekermann:

Yes. Well that is the problem but you ask most designers, that is the way. I am incredibly privileged that I actually like what I am doing. Not that I like all the projects, I certainly don’t like the business meetings, I never like writing proposals which I don’t do anymore. But, yes I am still incredibly lucky that I don’t have to…now, I don’t have to be in the office at any given time. I am always there before anybody else, if I do go to the office, and I will always leave last. But, in a way if I wanted to take a week off I could have taken a week off, I never did but I should have done. And I would fly to all these incredible places, I have been going back and forth to the States since ’87 and I have been to pretty much every country in the world, mostly on projects. I mean how privileged is that?

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And half of the time somebody paid for it. Now I pay my own flights but I have been so incredibly lucky to have a job that is by definition about communication and being international and learning languages. And I hate being in a country where I don’t speak the language. It embarrasses me, I hate going to places like Russia or China where I am pretty much blind. I mean I can read Russian, I can read the Cyrillic but I can’t understand what it says and that annoys the hell out of me.

Arkitektura:

So, do you really think it is luck, I mean what is luck? I don’t know, that word, I can’t wrap my head around it. I mean what is luck? You say I have been really lucky. Really? You probably worked incredibly hard.

Spiekermann:

Well, lucky just means you could be at the right place at the right time and not notice what is going on. You have to have your eyes and ears open obviously. I said my main characteristic is curiosity to the extent of that I read everything in front of me. I drive around, I memorize number plates ahead of me and behind me.

Arkitektura:

Wow!

Spiekermann:

It is an incredible mania and some of it sticks, not all of it but some of it sticks and I notice things, I know the color of buildings, I know why the windows are the way they are, I always know where north and south is although most people don’t. I know I am incredibly observant, I remember everything. I haven’t got a photographic memory but almost and that’s been my big talent, my curiosity. So that means that if something happens in a place at a time, I am about ready to absorb it. A lot of people aren’t and I think afterwards ‘that was internet revolution’ I live in Palo Alto and I didn’t notice, because some people don’t .

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

But I came to Palo Alto in ’87 because things were starting to happen, right?

Arkitektura:

Yes, I remember that.

Spiekermann:

So that is why I think I have been at the right place at the right time because I have also gone there. You know I didn’t live in London for eight years for nothing.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And now that I am back in Berlin I am at the right place at the right time again.

Arkitektura:

And you love Berlin, you said it was your city.

Spiekermann:

I love totally love it yeah. I wasn’t born there, I don’t have any loyalties really but everybody I know is there or either I know everybody there.

Arkitektura:

Yes [Laughs]

Spiekermann:

I know some of the institutions because I have been around so long. I have done a few major projects. And I have friends in politics. I feel very comfortable, I know every nook and cranny, I used to be a cab driver when I was a student and I just know my way around the town so much and it is just so nice.

Arkitektura:

Is it really like you walk down the street and you always run into people?

Spiekermann:

Yah, funnily that happens to me in London or even here, I mean that if I go to that little blue bottle café on Mission and Mint.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

I am there for five minutes and somebody will come up to me and say, “hey, are you Eric Spiekermann?” which of course I can’t deny and then they show me their latest project.

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

Because I have 320,000 followers on twitter and people seem to know me and in London, recently I was sitting at Ottolenghi in Islington at the restaurant.

Arkitektura:

Oh, I love Ottolenghi.

Spiekermann:

Isn’t it great! We are sitting at the back there, my wife and I, and just having a coffee. And there was this guy across there with two good looking women, he kept looking over at me and I thought, “oh God, this is gonna happen,” and of course then he gets up and he says, “Are you Eric Spiekermann? Can we have a photograph?” It was some graphic designer that obviously had seen my pictures some place.

Arkitektura:

I mean, it is not like you are an actor, you are a typographer. That is amazing!

Spiekermann:

Yes, but that is why it embarrasses me. My work by definition is apocryphal, it is not anonymous but it is apocryphal. You are not supposed to know the author behind it. You don’t go down in the subway in Berlin and look at the signs and say, “oh this is cool stuff this Spieker dude did,” no, you’re supposed to say, “oh, it is easy to find my way.” That is the point. I am not an author in that sense. I serve other people’s purpose.

Arkitektura:

But there is a wonder…I come from this very small radio world and there are celebrities in that radio world. Radio obviously is a sound medium, you don’t see a face.

Spiekermann:

Yes, of course.

Arkitektura:

And there are the celebrities and then it is actually very exciting to be a celebrity in this really selective [medium]. I love radio so I find it to be a magical, magical world. So there is something very special about that.

Spiekermann:

It is often useful, I mean I totally enjoy it. Like I was one of the MCs for the TYPO San Francisco last year and I am doing the stage again for the Berlin conference next week, a week after next. And it is incredibly easy for me because everybody knows me there and everybody kind of respects me, the younger kids you know. So I get a lot of credit, it just easy to approach people because they kind of know about me, that makes it easy I must admit but being recognized on the street I feel uncomfortable about it. Because what I am mostly known for these days is designing typefaces which by definition are unknown. I mean you use them, you don’t think about them. It is like bread you know you don’t think about the baker, you cut off slice of it and eat it for crying out loud!

Arkitektura:

Philip, my husband, is hiking the John Muir trail so he is buying all these hiking books and there was this hiking book and it was not a fancy book. But there was a long paragraph on the back about exactly the type that had been used by the book, who had created that type, why they used that particular type for this book. And I thought to myself, “my gosh! It is amazing how people wanna know that and they are allocating a page to it.”

Spiekermann:

They do now. That is unusual but I have always said for decades. I wrote it in my very, very first book back in the early eighties, that we should have a typography critic in the back of the New York Times as you have an Opera critic. I mean who goes to the Opera for crying out loud as opposed to people who read because everybody reads. Everybody and their mothers, sister, brother reads but it is like bread, I mean the restaurant critics don’t talk about brown or white bread. Bread again is one of those stables that you don’t discuss ever, and this is really bad, same with air and water. You will only discuss it when there isn’t any or when it is bad and type it is the same. It is the substance of communication of words where we read way more than we ever did. Because that’s what we do online. There may be images, there may be cat videos but basically we read, we read. Even if it is hundred and forty characters at a time, we read, we read like crazy. So type, a visual language, has become incredibly ubiquitous more than ever. And I am talking about western societies or the countries where people do read.

Arkitektura:

Yes.

Spiekermann:

And it is interesting because it has become accessible that people do appreciate it at the same time. I wish they would do the same…You are in radio which is words and people have no interest in language? I mean the bad grammar I get from Americans and even people very close to me, I have to keep correcting them. Less is the singular and fewer is the plural, “there is less people here,” I said no! It is fewer people here. There is less whatever, traffic but I have to tell them that. It annoys me that language is again something that we just so take for granted that we don’t look at it properly.

Arkitektura:

Or punctuation!

Spiekermann:

Oh give me a break! It’s one of my pet peeves. I am very good at grammar in a few languages maybe because I look from outside and I learnt it properly. I must admit I am a grammar nerd. I like grammar because it is that what holds it all together.

Arkitektura:

It all is connected. So one of the questions I read was, “oh, you know, what do you do at the end of the day?” and your answer was, “I like to read.” So I was wondering what do you like to do when you are not working? Where do you like to visit? What do you like to explore?

Spiekermann:

I had a little, almost an epiphany yesterday, I was in a place near here. We were in Potrero, I was over at the San Francisco Centre For The Book, which is De Haro and 17th, so it is couple of blocks from here. They had a little dinner there for their teachers and I am on the board for some reason because I donated them a printing press at one time. So, I was there and I rode up in my bike, I came over the ferry from Tiburon which is great and approaching San Francisco by the sea is the proper way. It is like Venice: You go to Venice, you got to go take a water taxi or the Vaporetto because you gotta go by water and the same is San Francisco, approaching them is quite different. Rather than coming in from the stupid Airport which is to the southern burbs. And I realized what I really like best is riding on a bicycle in decent weather at my leisure. I wasn’t going too slowly, I wasn’t going too quickly and then I went over to Hayes Valley, had an ice cream at Smitten, went to see a friend in Linden street or whatever it is called or avenue.

Arkitektura:

Yes, Linden.

Spiekermann:

Oh that nice little area there, and then I had a coffee and as I walked away from having a coffee in Linden, two friends, Chinese friends who I haven’t seen in five years called me, so we had a chat and I thought, “my God! I am so privileged”. And I love that best in life, I love cycling around in cities because it is quick enough to cover quite a distance. I mean I probably did about fifteen miles that afternoon, but I can always get off, unlike a car, there no parking issues. I can get off, I can have a coffee, I can stop and talk to people but if I want to I can do ten/twenty miles an hour and get out of there very, very quickly. Which I had to do at the end of the evening to catch my ferry at 7:30 to go back to Tiburon, so I realized that if anybody asked me, I didn’t realize they were gonna ask me what is my favorite thing in life, it probably is, other than some of the more intimate things maybe, is to sit on a bicycle and go around cities because it is the right rhythm, the right space, you are high up even higher up some SUV’s. So, you see everything at your leisure, you are moving yourself which is also healthy. It is a great form of transportation. I am a total bicycle freak anyway and it was just so nice yesterday. Mind you, I do like espresso and ice cream and I always chat with people about the roast and the way they make things. It was such a perfect day.

Arkitektura:

I love that.

Spiekermann:

And whether it is in Paris or London, I ride bikes, which some people don’t understand. I ride bikes in Berlin all the time. And it is not so much about the bike but it is just being so close to the city but yet to be able to get away from it. As a pedestrian, it is a little bit more difficult , you know walking is kind of nice but if you really wanna cover distance you just can’t speed up. On a bicycle, I can go five miles an hour, I can go twenty miles an hour. Walking is walking, is walking, so riding in cities is just…Oh! It is perfect.

Arkitektura:

And plus when things works out so wonderfully where you move fluidly from one thing to another and you discover and then this happens, that happens.

Spiekermann:

And you discover some stuff. I mean I cycle in London and what not, and every time when I come in…We have a house in north London, I go into the Centre, I take different ways and I never look at maps, I actually kind of know where I am going kind of and I go diagonally. I discover, especially in a place like London, I discover backstreets and little squares and alleyways that I have never seen before that I would never find anywhere unless I happen to just ride by there. It is really quite liberating.

Arkitektura:

I love that feeling too. Your office was right by the Berlin wall, so you were witness to, of course, the wall coming down. Can you describe to me a little bit about what that experience might have been like for you?

Spiekermann:

You know that is one of those things we talked about, being at the right place at the right time. I was so close to that, I just totally overlooked it almost! I remember being here and this is in October ’89. I was in San Francisco hanging out with my friend Bill, I have already had projects here, I was sitting in Redwood city in Bill’s bungalow and the news came over from the Hungarians opening up. They were the first guys to open up so all the East Germans went into Hungary and then there were 500 people that went to West German embassy in Prague so it was all happening and I was saying, “Oh my God! This is really exiting!” but I never for one second thought even at the time that the Berlin wall will ever come down. I moved there in 64 middle of the cold war. I just thought, “Ok maybe the East Germans will have a little outlet and they will let some people go or maybe they can get visas to leave for a few weeks. So I was totally not aware of it and then when I got back to Berlin, this happens in the evening of the ninth of November, that by some bureaucratic mistake some guy said, “Oh, you know we are opening the wall and our people can go to the West”. Which was actually a mistake but it happened and they stormed the border crossings and East Germans had to open because otherwise they would have had to shoot at their own people, which they didn’t want to anymore. By that time, I went to bed earlier, didn’t hear the news. I get downstairs at quarter past seven on the 10th to get my papers which were at the doorstep. And there were these two guys sitting there, among the very few friends I had in East Berlin, because I couldn’t get over very easily and they certainly couldn’t get over and I looked at them I said, “What’s happened, did you run away?” and they said, “no, no, the walls are brought down!” and I said yeah, the Pope is a Catholic and la,la,la I know all the rest of it. “No, seriously!” I said, “give me a break, no fucking way!” And I pick up the papers, there was the wall and it was down and I how did I not see it. I wasn’t there and I lived in the middle of it! I mean I was a day late, they just left at midnight and I was the only person they knew in the west, so they were driving around and then they have been sitting on my doorstep since five o’clock waiting for light to come up because this is November. They brought some East German Champagne which then by the time my people came to the office we’d finished and then we went to the wall and danced on it like everybody else. But the whole political environment, all the goings on I have since read and learn about but at the time it was too close. I mean the wall was like in your face so much that you couldn’t see beyond it. And I would have taken any bet that is was there to stay for another fifty years. But ironically, that September ’89 before the shit hit the fan, as it were, we rented that famous office, the only building left in what is now Potsdamer Platz which is now the center of Berlin. It was one building left from the war. It was like literally three feet from the wall, at the back door it was the wall, you could reach out and touch it. We rented an office there in September thinking, “this is so quiet, there is plenty of parking, there was rabbits on the lawn outside, this is so idyllic, we are in the middle of nowhere right by the wall.” And, of course, by the time we moved in after Christmas, around the first of January, I remember putting furniture in there on Christmas eve and by that time the wall had kind of more or less disappeared. There was what they called the Polish market outside the wall so everybody was just crazy and I gave out dozen interviews to NBC and all these American stations because I was stood in my office on the wall and they said, “what is it like these days?” I must have answered that question a hundred times because I was the only person there. Of course, we quickly moved away from there again by the next August because it was unbearable. And this building is still there in the middle of all this new stuff. It is the only old building left so this is how I miscalculated the situation. It surprises me and I regret in a way not having had the foresight because I would have enjoyed the changeover much more. I was so in the middle of it that while I went out to East Berlin itself, I never had a perspective on it. Now I do but, like I said I was so close, it was incredibly exciting. But it might have been even more exiting if I had had a more of an intellectual..it was very emotional it wasn’t intellectual. Everything now is post-rationalizing.

Arkitektura:

It is fascinating yes and talking about post-rationalization you were saying once that mistakes are incredibly important. It is not about doing brilliantly, it is about actually making mistakes. What are some of the mistakes that you’ve learned the most from would you say?

Spiekermann:

By the way everybody says that, there are of course mistakes. I mean the whole thing about experience is you can’t gain experience if you don’t make mistakes and experience will prevent you from making more mistakes, over time that will work out. I make fewer mistakes now because I made more in the past. So the biggest mistake, one of them certainly, was not keeping my first marriage together, not that I regret meeting my second wife, but it would have been nice to be able to see what was happening and you know act before it was too late. I think everybody who has been through one marriage regrets that because you like each other at one time, you are in love with each other and we had a child together. And not being able to fulfill that…And I am very monogamous, or these days at least, so I find that a bit of a failure. We managed to stay good friends and I am very, very happy that I am with Susanna now but still I think that is a bit of a failure not being able to keep that first relationship. Although most of us can’t do that for some reason, so that is one thing. The other mistake I did is, the big, big mistake I did when I…My first company was called Meta Design which I started in ’79 and then I went on and on and then I brought on two new partners in and I made one mistake there simply because I didn’t want the conflict. As two people who are brought in deliberately because the thing was getting little too big for me and I hate doing administration. So I brought in this banker guy as our COO and a woman who was kind of colorful visual designer. I am a much more theoretical/structural black and white kind of guy. I needed somebody who has that, in that case the female intuition, the artistic part, which I don’t represent. It seemed like a good mix from outside and everybody warned me, “don’t give these guys full shares,” and I said, “oh, come on! Let’s divide it by three,” which of course is rubbish. That means you have no majority, it is totally stupid and of course over time me being the big old daddy, always traveling. They got a little, at least one of them got a little jealous of me because I was the big famous guy they stayed at home and did the work kind of thing and I kind of knew it but I didn’t want to deal with it. And when I started dealing with it; it was too late, they sort of pushed me out, the company went bankrupt and got sold and all the rest of it. They threw away my archives, it was really, really like a bad marriage, you know where the wife then kind of burns your socks kind of thing just to erase all traces. I really messed that up, I should have known that I should have kept 51% because it was my company. By that time, I had been going for twelve years and I had a reputation and I had work and I brought in two newcomers. Not because I am generous, I just was lazy, I was too lazy to deal with it, I didn’t want to face the conflict, I was intellectually lazy, I was afraid of like most…Come on, men are very afraid of dealing with issues and I don’t do that as badly anymore but it was just that I knew I was kind of making a mistake but I couldn’t be bothered ‘ah it is gonna be ok’. You know that sort of singing loudly so that you put your own fears at rest because you just add some other noise to it. It was the wrong move, I kind of knew it and I didn’t deal with it until it was too late, until I had alienated everybody so the fact that the whole company split up was easily half of my fault. I don’t think my partners behaved very nicely but obviously I wasn’t to be reckoned with. So that was the one thing I regret most. And that is the only major mistake I remember and I do regret not having finished my studies but you know what I can go back to University if I want to tomorrow.

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

And I am sure I wronged some people, I have judged some people too harshly but I think everybody would say that.

Arkitektura:

Of course.

Spiekermann:

You know I didn’t speak to my Dad enough before he died, that is also the normal thing, we never had time for each other.

Arkitektura:

Really?

Spiekermann:

Yeah, you know I was busy, he was busy, he was the wartime generation, he was born in ’21, that generation didn’t really talk about the issues, I mean towards the end we had a few conversations about what happened in the war and stuff. And I should have probed a little deeper because it is interesting. I mean that generation went through a lot of stuff and my mother was the same. She was same, born in 1920, she lived a little longer but all the things that went on, they started talking about them and I could have pushed, I could have asked, I could have been showing a little more interest. I always think, “oh you know, well I will ask next week, I will ask next year,” and then suddenly my father was dead. Because I see that now with my son, that we talk way more than my Dad and I ever did. We have pretty much a sort of almost like a brother relationship not entirely but it is kind of you know, we hang out way more together and share a lot more interest and we’ve travelled together, we’ve been to Japan and Australia together and stuff. So it is kind of like a different relationship, way more, and partly because I am aware of the fact that I never got into what drove my father. That is something for the shrink but that is really the major regrets I have.

Arkitektura:

I really appreciate your candor so much and yes it is very difficult to keep a relationship together when you just started at such a young age. I mean you were a teenager when you got together with your wife and thank goodness you guys are still friends. And as for your son, well, you know, I am only twenty years apart from my Mum too and it makes a huge difference in that we are like sisters in many ways because our generations are not that different.

Spiekermann:

That was different with me and my Dad. I mean, I was born in ’47 he is born in ’21. He is only 26 years older than me but a totally different generation. And then war makes such a difference, they were so much older than we were. My son and I…I was born in ’47 and he in ’68 as I was at University. It is not the same generation but we are way closer together like you guys are these days, it makes a lot of difference.

Arkitektura:

And your parents, were they either of them creative?

Spiekermann:

No, my father had a–. Well he was charming.

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

Good looking, he had hair. Unlike me, which on the radio, lucky you can’t see.

Arkitektura:

[Laughs]

Spiekermann:

He was a little short so he had a little, I wouldn’t say a Napoleon complex by the way Napoleon wasn’t short that just a British propaganda.

Arkitektura:

Misnomer.

Spiekermann:

Yes, but the Brits perpetuated that myth. He always regretted that he spent his best years in the war underwater in a U-boat in which not many survived and he hated the Nazis for that. Having taken away his best years, he got out of the war when he was almost 25 and he just hated that. He taught himself French later and a bit of English. He could have been well educated but after the war he had to do things; he was a mechanic and then he drove a truck and he regretted that. He was charming but he didn’t have the right education. And my mother was just a simple post office civil servant, way brighter than was required for that. Both of them, if it hadn’t been for the war, would have had a proper, I wouldn’t say an academic career but they would have done more for themselves. That is why both of them were, if not pacifist, they certainly didn’t want me to join any army. That is why by the way I went to Berlin because Berlin at the time didn’t have any draft for the German troops. That was all Canada I guess.

Arkitektura:

So were they witness to your success?

Spiekermann:

Yes, of course they were. I mean my Dad was really proud, you could tell because I had sort of done what he hadn’t done because he was always an entrepreneur. He always did stuff and he taught himself a lot stuff and I was kind of the same. He never had one exam and my Mother was also very supportive. I mean she always looked after my files and did my bookkeeping and stuff.

Arkitektura:

Really? [laughs]

Spiekermann:

And iron my shirts which I kind of hated and like you have your Mother come when I lived on my own for a long time in between, my Mother would be there every day and iron my shirts which causes a little bit…She had nothing else to do and I love ironed shirts and I hate ironing myself but is also kind of like ah!

Arkitektura:

But it is such an act of love.

Spiekermann:

You are in your fifties and your mother is there every day, it is kind of you know it was good for her because my brothers and sisters were all elsewhere. So I was kind of like the one left behind and she thought she needed to look after me but she didn’t. It was more like I looked after her but that is also ok.

Arkitektura:

Totally ok, totally ok. And your son he is involved in sound production in music?

Spiekermann:

Well, he is a musician. He learnt sound production at my brother in-law’s studio way back in 10, 15, 20 years ago. 20 years ago I think or whatever late 90’s. Yes, he lives in London, he is an unemployed musician which means he is penny less. He does write translations every now and again, German into English, because he is bilingual obviously and he doesn’t like that very much. It just happens to be better money than what he does, which is schlep furniture, he does odd jobs because his music doesn’t pay. Yeah, he is a bit of an artist in that sense.

Arkitektura:

Yes, we talked about the things you regret. What is something that you really, really think, “I did this brilliantly, I did this really well, I am really, I am just, I am so proud of this”?

Spiekermann:

Well , I managed to have a network of people that I have worked with. I didn’t do this deliberately. I didn’t say, “I am gonna gather all the great designers of the country around me and I am gonna make them all famous,” of course I did not. I did my stuff and I brought in people mostly because I like them and I wanted them around me and they brought in the other people. And I now I am the Daddy in the company and they say when I am there the mood changes because I praise people but also criticize people. Because if I criticize a 25 year old designer, it is not personal because I am so far away from it, I can do that, I am not competition. And I have never been in competition with the people I have hired and I think that is the one thing that I’ve really done well. And that is I think my single most achievement, that I have managed to build a network of people who now all know each other. A lot of them work with each other, they are dozens of offices in Berlin and elsewhere of people that met each other at my place and then realized that they had something in common then moved on, like you have to move on. You know, you can’t stay at your first job more than two or three years, that is boring. And I can walk into them even though they are officially competition maybe. And I am always welcomed and I so enjoy that I have my own little community there because I have never done anybody any harm. And I have written I think about sixty testimonials for people who wanted to go to become professors. In Germany, you have to give couple of a recommendations. One of the for accreditation, you have to have some people write up to say this person is suited. And I have done that for, I have looked it up recently sixty two professors in Germany, in England and America teaching at Universities that I had sort of enabled. And that is a pretty good life’s work, I mean I can be pretty happy and I think most of them are good teachers, none of them did it because they wanted to get a pension and all of them did it because they like doing it. And you know, so I have been teaching and I know most of my ex-students still. I don’t teach anymore because you don’t teach over 65 in Germany. So I think I have a little community which is very, very comfortable.