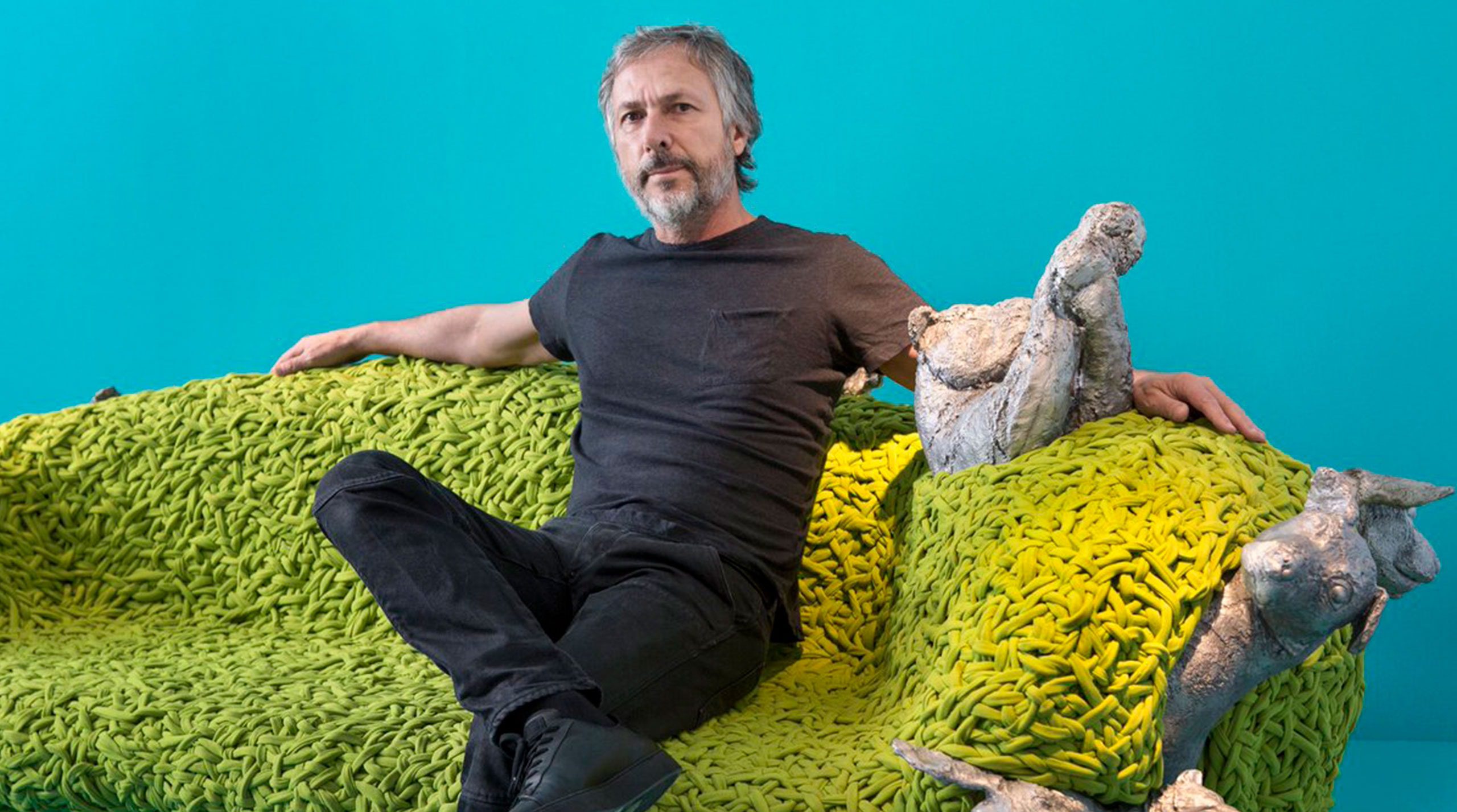

The Campana Brothers have been making their indelible mark furniture design for nearly three decades. In that time, they have won numerous awards, have had exhibitions in museums all over the world, including MoMA, both in New York and Sao Paolo, the design Museum in London, the V&A in London, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Architecture and Design Museum in LA and numerous others, all the while breaking barriers in their work and use of mediums. Their work is like none other and they believe in the power of joy. In this interview, we speak with Humberto Campana about his childhood, what led him to becoming a creative and how he’s started to give back to his community.

Humberto Campana:

I like to have fun. I gave up law in order to have fun in the life. Fun in a sense of do things that pleases me; freedom. I like to be free. What matters for me is to be free. The most important thing for me is freedom.

Arkitektura:

That’s designer Humberto Campana, half of the dynamic duo known as the Campana Brothers, and this is Design in Mind, a podcast series from Arkitektura, which has been a hub for international designers and brands in America. My name is Tania Ketenjian, and Design in Mind candidly explores the lives and work of some of the most inspiring designers and design thinkers from around the world.

The Campana Brothers have been making their indelible mark on furniture design for nearly three decades. As you’ll hear in this interview, they grew up in the countryside and as young adults took different career paths. Humberto studied law, and his brother Fernando studied architecture, but uninspired by a career in the legal field, Humberto took the radical leap of moving to Bahia and satisfying his creative inclinations by making things with what he found, namely seashells. During the busy holiday season, he asked his younger brother Fernando to help them with deliveries, and a collaboration was born.

Since that portentous moment, the Campana Brothers have won numerous awards and have had exhibitions in museums all over the world, including MoMA, both in New York and São Paulo; the Design Museum in London; the V&A in London; the Centre Pompidou in Paris; Architecture and Design Museum in LA; and numerous others, all the while breaking barriers in their work and use of mediums.

We spoke with Humberto Campana from the Campana studio in São Paulo, where they have been working from for most of their career. Before we turned the mics on, Humberto was showing me something he had just made, a small object, a chair made by hand. As he said, making things is what has kept him centered during this wild time of COVID. Please stay tuned.

I gave up law in order to have fun in life…the most important thing for me is freedom.

Humberto Campana:

I grew up in the countryside, in a small town named Brotas. It is two hours and a half by car from São Paulo. My grandfather came from Italy to grow coffee, so he was used to have coffee plantations there. All my childhood was living in the farms. The city where I grew up, it was very small, 5,000 inhabitants at that time in the ’50s, and there was no pavement road to São Paulo. It took, at that time, six hours by car to go to São Paulo. It was adventure.

My father was agronomic engineer, so I live that life of farms. My father was used to take me to the farms. He teach us how to respect nature, how to be protect, all the plants. I love to grow plants, to plant trees. I love this. So I learn all this, and besides, the landscape there is beautiful. It’s gorgeous. The city, this small city, has 38 waterfalls, rivers, that you can do rafting. It’s very beautiful, the area.

One thing, it was good because we didn’t have contact with São Paulo, very few, and we had no TV sets, just a movie theater there. That was amazing because the owner of the movie was an Italian guy, so he brought all the Passolinis, Fellini. A small kid, myself, I went to the cinema to see those films of Kubrick or even Far West. All kinds of Brazilian movies. It was very rich. Whenever… the movie, we went there in the evening and during the day we tried to represent things that we saw in the movies, doing objects in clay, bamboo or cactus, stones; whatever we have in hands. We worked with the hands.

It was interesting because people was used to ask me what I would like to be when I grow up. I was seven years old. I told them I wanted to be indigenous. I want to live in the Amazon. So the contact with nature was very close all the time. It was very rich in terms what we are today, because I guess today we recreate hybridism between the countryside childhood… Can be São Paulo, Tokyo, Italy, whatever. Yeah, we try to represent these two universe, two forces.

Arkitektura:

I have a lot of questions, but when you finally decided to locate in São Paulo, how often would you go back? Did your parents stay there?

Humberto Campana:

They always lived there. I came to study law here in São Paulo, but I was used to go every weekend there. I take a bus or a train. At that time we had trains, very good trains. There was a time that I gave up my seat. I didn’t want to go back. Now I’m coming back, I guess, with the quarantine, so I’m coming back. I have a small farm there where I’m taking care again, planting trees, doing art installations there. I plan to make that place a garden, a sanctuary of plants and animals. Yeah

Arkitektura:

But what surprises me is that you decided to go into law, maybe because you wanted to do something traditional.

Humberto Campana:

I want to please my family. I was so immature, so child. I wanted to leave my city. What I want, I want to leave my family’s house. I want to be free. I didn’t like mathematics at that time, so I choose something that connects to… I like to literature or writing at that time, so I went to law, but at the first day I realized that wasn’t not my trip. But I stayed five years there, spending nothing, doing nothing. When I got my diploma, I gave it to my family and I told them, “Now I’m going to take care of my life.” Yeah.

Arkitektura:

Did you do that? Did you actually say that?

Humberto Campana:

Not in these words, but yeah. I moved to Bahia. Bahia, it was a synonym of freedom at that time. Mick Jagger, Janis Joplin, all those creative minds in the ’70s were used to go there, so it was a place of freedom. That time, there was a dictator military here in Brazil, but there, no, it was untouchable, so all the crazy people was used to go there. So I went there and I start my living there in the countryside of Bahia.

It was a city near the ocean, and I was used to pick up seashells in the ocean, clean them, and start making frames of mirrors with seashells. I told myself, “I want to make my life with my hands.” I told [inaudible 00:08:50], “I want to construct my life with my hands. I think it’s very honest; can be honest. I don’t want to depend off nobody to…” So I did all of those things. I was used to pick up the shells, clean them, create, knocks people door to sell, or shops; doing all those things by myself. Yeah.

Arkitektura:

Yeah. Bahia, my dad used to go to Brazil and he would bring me all these tapes of music from Bahia. I had this vision of that part of Brazil as this… beauty and freedom, and creativity and passion and fire. I can imagine living there, just how that… It’s hard to not want to be in that mind-state forever. It’s hard to maintain the roots of what you loved when you become really well known and established, so how do you do it? How do you get back to that?

Humberto Campana:

I try to be myself all the time. Yeah. I guess things has changed in my life. Nowadays, I have a better life in terms of living, to have affordable, but nothing has changed in my life, really. It sounds pretentious or hypocrite, but no. For me, really, I’m very humble because I know all the steps. I know each step was so difficult to achieve. Yeah, nothing has changed in terms of… I have the same friends, I go to my hometown. I don’t like to be in the middle of the crowd. I’m a reserved person. I don’t like to show off. I think my art, my work, needs to show, not myself.

I’m not a promoter of myself, and especially more and more I’m getting mature, I like to be alone or silent. Yeah, but things has not changed. Not at all. I say this with very… conscious about this. I still work in the same place. I am here since 1992, in the same place. It’s funny because people come here, was used in the beginning, the taxi driver told them, “Are you sure that you want to be here?” 10 years ago, here was a no-go zone in São Paulo. Now it’s becoming fashion, trendy, but things has not changed for me. No.

I like the process, to be with the artisan. I love this, to be in the workshop, working with the artisan. Not doing myself, but stay with him, “Let’s go back this way,” weaving. I love this, this contact with people. Create with the hands; people with the hands. This makes my life… it makes precious for me.

Arkitektura:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). Mm-hmm (affirmative). Same with your brother?

Humberto Campana:

Fernando, he likes to stay at his home. He doesn’t come so often to the studio, but he has the eyes of… Sometimes I’m very connected to the object that I cannot see it, so he comes sometimes and see with the faraway eyes so he can give me directions, which is very good.

Whenever we were kids, we used to play together. Yeah, we are very good friends, one of each other. It’s not easy to work with a brother, but we pass so much turbulences, me and him, in terms of, “Are we going to stay together or not?” There was one time that we’re kind of connect so we didn’t what we are, so it was important for us to split in order to respect each other and maintain the same respect as we were used to be very close. In the past, we are used to do, for instance, a lecture, we both were together, or sign a contract and go to Italy, both. It was so intimacy. That was very bad for us. Nowadays, we grow up in terms… now I can do the lecture, or you can go to Italy, work there. I can stay here. So it’s easier, but it was difficult to come to this conclusion. Wasn’t easy.

Arkitektura:

Of course. You’re figuring out your roles. I think that’s true in every relationship, “How do we fit? What identity do I have in this partnership, and how do I clarify that to myself and to the world?”

Now, I know this story, but I don’t think our listeners will know, so I’d love for you to share a couple of things. One is the story of how you and Fernando first started working together. I know what happened, but I’d love for you to say. Then that MoMA show, not receiving the fax. So, you were making these frames with the shells, and I think you were selling them.

Humberto Campana:

Yes, and I was used to sell them in magazines here in São Paulo, shops, and one day I call Fernando to give me a helping hand to delivery those mirrors during the Christmas. So he came here, he was finishing the architecture school at that time, and Fernando, he was lucky to have worked in the Biennial of São Paulo. He was assistants of Keith Haring. He was very close to those crazy people, creative minds, so he start giving functionality. He was used to stay one month, and then he was take care of his self, and he stay. He stay, growing things, and he start to change my mirrors in terms of point me out new direction, opening my mind to the world, because I was doing so naive things, very naive. He was, “No, this is happening now.” So he pushes me, pushes me, in order to bewhat I am.

It was fun because in 1989 we create a collection of furniture, iron furniture, very dystopic for the time. It was very rusty, aggressive, and we name it The Uncomfortables. For a long time, we were known here in Brazil as, “You are the Uncomfortable Brothers.” We didn’t sell nothing. It was difficult to making a living doing design because we did that.

I think Brazil is a continent, has a continental dimension, and today I note that I didn’t want to follow the modernism rules. I think it doesn’t fit here because we are so rich in terms of popular culture. We have the indigenous, the Afro, the Armenian, the Lebanese, the Italians, the Japanese. All this hybridism is very rich. Also, with the materials that we have, the climate, the nature.

So I think we are not black and white, and at that time we didn’t want to follow the Brazilian modernism. We want to create things with nothing. Showing we come from a beautiful country, but we are not wealthy in terms economically wealth, but we can be very elegant to present with very simple solutions. I think we believe that we can dialogue with the other culture. So that the way that we start to be known in the design community.

One day, it was 1997, Paolo Antonelli came to Brazil and she visited the studio, and she liked our work. One time she was working at Domus magazine, so she get contact with our work. One year later, she call Fernando and say, “Fernando, are you not happy with my invitation for my show?” “But what? I didn’t know that.” “Ah,” she told him, “I sent you a fax with the official invitation,” but at that time we didn’t have money. We were completely lost. We didn’t have the paper for the fax, so… It was funny, how things… After that, things has changed. The MoMA show was a split or-

Arkitektura:

A defining moment.

Humberto Campana:

A defining moment. Yes.

Arkitektura:

Yeah. Also, I thought that what was interesting about that MoMA show, there’s so many things that come together, the serendipity and all the things that happen that are magical that you can’t explain.

Humberto Campana:

I think life, for me, is magical because things happening in this way. My first chair that happened, I was rafting in the Colorado River. One day my boat flipped and my life guard was open, so I got inside a whirlpool. It was so strong that finally I succeed to save my life, and four hours later I design a chair with a spiral. I came to Brazil, I was working with iron, with fire, so the piece that I take from the iron, Fernando construct the other chair.

Things in my life happens in this way. It’s very magical. I’m not rational. I’m very intuitive. Very. Sometimes I dream about shapes and chairs or projects, and things happen in this way for me. I’m not a strategist. Not at all. I live life to bring things to me, and then I try to digest in terms of creativity or surviving. I don’t know

Arkitektura:

There are things in life that are magical, you can’t explain them, and that’s good. That’s good. It’s beautiful. It’s what makes life. It can’t be just explained and rationalized. You have to feel it.

Humberto Campana:

It was so funny because when I gave up law, I was completely lost, completely lost, but at the end of my mind I knew that something good would happen in my life. It is strange. Yeah. I knew that something good would happen that I’m not going to live in the streets or be a drug addicted, all those. It’s funny. I think that I’m a medium.I believe in this. Really. Really.

Arkitektura:

Yeah, like ideas come to you and you have the ability to manifest them.

Humberto Campana:

Exactly. Yeah. I came here in order… like a mission, to bring people’s…I think kids loves our work because they connect with the childhood immediately. I try to bring all these elements in my work, the childhood, the memories of affection, love, or funny, all these things, the elements in the work

Arkitektura:

Yeah. What’s interesting about calling yourself a medium, and it really does connect with you saying that you’re humble, is that means you’re not taking ownership of your ideas. I know that you do, I’m sure you do, but there’s a lot of humility in saying that because you’re saying, “I’m a vessel.” It’s an interesting way of saying it. I’ve interviewed a lot of designers, a lot of very famous designers, and it’s the first time I’ve heard that. I love that.

Humberto Campana:

I think life has changed so much. Why to be so pretentious, so snob? I hate this because life takes care of us in terms showing, “Now, today you are on the top, but tomorrow you can be in the bottom. Don’t drink so much because you can have a very bad hangover, so easy going, please.” I believe in this.

Arkitektura:

I believe in that too. What I really think, and you should correct me if I’m wrong… What I think is interesting about that first chair is when I think about you getting caught in a whirlpool, water swirling, fluid, terrifying, terrifying, but there’s so much fluidity. It’s such a different medium, it’s such a different element than metal, which seems so rigid and hard. Am I wrong about that? What a contradiction to try and emulate or recreate or imagine this experience of being caught in a whirlpool manifesting in something made out of metal or iron. It seems really interesting.

Humberto Campana:

Because at that time I was connected to iron. I was taking classes, iron, because I would love to be sculptor. At that time, I was welding, cutting metal with fire, so I was very connected to that material. That confront with the death open a portal, a huge door, in order to… “Now I am free.” I can investigate all these things that had stayed inside my… for a long time because I was afraid, also, to show my family that I was an artist.

My family was Italian, very Catholic, very rigid in terms… so to be an artist was a synonym of a lot of bad perversion. Yeah, I came from a family with… there was military, all those very traditional… so it was important to get the confrontation with death in order to open; to know, “It’s this that I want to do.”

Arkitektura:

Another defining moment

Humberto Campana:

Yeah. Exactly.

Arkitektura:

The MoMA show, the fact that you had to make work so quickly, I think is so interesting, from August, because you found out in August and the show was in November. That’s a crazy timeline, and the excitement of, “This is my opportunity. This is my opportunity to… MoMA.”

Humberto Campana:

Exactly. Yeah. We got so energized with that invitation, when we knew that. Me and Fernando work all night long, all days, in terms of doing all those things in a very… Yeah, and it worked. We didn’t have money to send the pieces. We didn’t have a sponsor for the Brazilian government. We found sponsors. We did all those things, I don’t know where we found them, and yeah, in a very short time.

Arkitektura:

It changed your life. The element of childhood and that connection that your pieces have with children is intriguing to me, and it’s particularly intriguing to me because of the work that you do with children in favelas. Design, especially the design that you’re in, the milieu that you’re in, with Salone and all of these major brands that are… They’re expensive pieces to have, but you’re finding a way to work with children whose minds are not open to the possibilities of their life. Can you tell me about that experience, what you’re bringing to them through what you’ve experienced?

Humberto Campana:

It was interesting because 2000, in the beginning of this century, we’re looking for doing upholstery with the things that wasn’t the traditional methods. So we are working with plushes, doing the plush chairs. One day we bump into a doll, a Brazilian doll made by a community in the north of Brazil, in Paraíba, a traditional craft there. We did that, we manufactured a chair with that, those dolls that we bought from them. All of a sudden, one day they call us and they told us, “You changed our project because, with the publicity of your chair, we start to selling our dolls all over Brazil and we construct a workshop for us.” That single moment was not about, “I’m going to do social rescue,” nothing, just I was investigating a new way, working with the Brazilian traditions, and we change people’s life.

From that moment, we create a institute, the Instituto Campana, where are we teach in favelas where poor people in fragile situations or on drugs. The idea is to grow this. Unfortunately, with the COVID, all those things needs to stop. In the beginning, I was used to go to the favela to teach the kids, and I knew very close their reality. It’s so close to [inaudible 00:30:16], the examples. I remember that I was telling them, “Oh, let’s make toys. Please design toys that you like.” Most of the toys were bombs or guns. All those elements connect to drugs. I ask them, “What you want to be when you grow up?” “Oh, I went to go sell cocaine. I went to be a drug dealer.” So it was very… that reality.

So instead of going there, I start bringing them to my studio in order to give them another universe. So we was used to take them to museums, to films. Yeah. The idea is I want one day to make a school of vernacular, the hands, weaving, embroidering, welding, carpentry, all those things that is made with the hands. I want to work on this. The idea of the Instituto Campana is to create this school, and we are looking for sponsors to make this happen. I believe that we will, I think, because I try to put my experience to the kids to show them you can transform this chair. It’s just you need to have eyes. There is no secrets. You need to see beauty. For me, it’s easy because I tell them my experience, or even for a doll’s house for the drug dealers, or alcoholism. I try to pass my experience working with the hands and try to insert in their minds passion, passion for the material; what’s important.

Arkitektura:

And a new way of seeing, like what your brother did for you, like opening your mind. I love that feeling when someone opens your mind to see something in a completely different way. It’s very exciting. I want to read you this quote that I read that you said in that BOMB interview: “We probed the artistic potential of discomfort, the poetry of the distorted, the poetry of error.” Do you remember this?

Humberto Campana:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Arkitektura:

Do you remember saying this? It’s such a good quote. We’re in such a moment of discomfort right now, and so how do you find poetry in that?

Humberto Campana:

I think those things, they are elements to us to push us to poetry in order to survive. I tell about myself, the way that I find to be mentally healthy is to try to have an idea in mind in order to survive it. Every day I read in the newspaper so bad things that now I go to my studio, I want to create, I want to do manual things. I’m doing things like this these days. Yeah, I got all those bottles. I’m trying to do sculptures.

Meanwhile, when I don’t have nothing in mind, I’m doing those things or big projects like art installations in the countryside. Yes, I don’t want to stop. I’m drawing a lot, doing things, find ways to put my mind… connect to something in order to be depressed. Because I’m very sensitive, things can be very destructive for myself. I can go easily to other ways, also, of depression, and a way that I found is doing things like this, working with the hands. These are all glued, like seashells. Can you see?

Arkitektura:

Yeah. It’s amazing how you come full circle sometimes. Well, it’s a strange time in this world right now, but there are many beautiful things as well.

Humberto Campana:

Yeah. We need to be resilient, to plant trees or whatever. Do things that fulfill our life; minds. Why we are here? We are not stupid. We need to change things. We don’t give up…this stupidity that’s happening right now.

Arkitektura:

Are your parents still alive?

Humberto Campana:

No, they pass away. My father, 20 years ago, and my mom, 10 years ago.

Arkitektura:

Wow. So, did they witness your success?

Humberto Campana:

My mom. My father, no. My father, he pass away very young. My mom, she came to the MoMA show. Yeah.

Arkitektura:

What was that like? How was that for her to see that?

Humberto Campana:

At that time, she has never traveled abroad or get inside a plane. For her, it was so… Yeah, it was wonderful. Yeah. She was very proud.

Arkitektura:

What are you proud of?

Humberto Campana:

I’m proud to change the way that people make things in Brazil. I think I contaminate a whole generation of young designers to see design or life in another way. I see so many young designers doing things that… the seeds, things that I put, and now I see people… Yeah. I’m proud to change this, especially in Brazil, to change this mentality of modernism, to be colonized. What refuses this, cultural colonization. It’s hard because it’s so impossible for you not to get contaminate by the other’s idea, but I try to make a portrait of Brazil with the elegance, with nobility, humble also, with simple materials. We can create the fake diamond with the plastic.

Arkitektura:

With color, with vibrancy.

Humberto Campana:

Yeah. I think we change this. Yeah, so I’m proud of this.

Arkitektura:

Your work is obviously beautiful, but it’s more your character that I’m interested in. There are many people that live their lives the way they think they should and then they turn around and they think, “Why did I do that?” they’re like in their 70s, but you had the bravery to not do that, and look what it created. So I’m glad you did.

That was designer Humberto Campana of the remarkable duo known as the Campana Brothers. Their work is in the prestigious roster of other furniture designers at Carpenters Workshop Gallery. To learn more, please visit carpentersworkshopgallery.com.

Design in Mind is a podcast series from Arkitektura. Based in San Francisco, Arkitektura curates the best design from around the world and makes it accessible through its retail spaces, live events, when possible, and this podcast. Design in Mind is Arkitektura’s way of honoring the life and work of some of the best designers today and celebrating the magic and beauty of design and design thinking.

Design in Mind is produced for Arkitektura by SOUND MADE PUBLIC. I am your host Tania Ketenjian. To hear more, please visit arksf.com or go to iTunes and subscribe to Design in Mind. You’ll see many wonderful interviews there. Rate the show, tell us what you think. Thanks so much for listening.