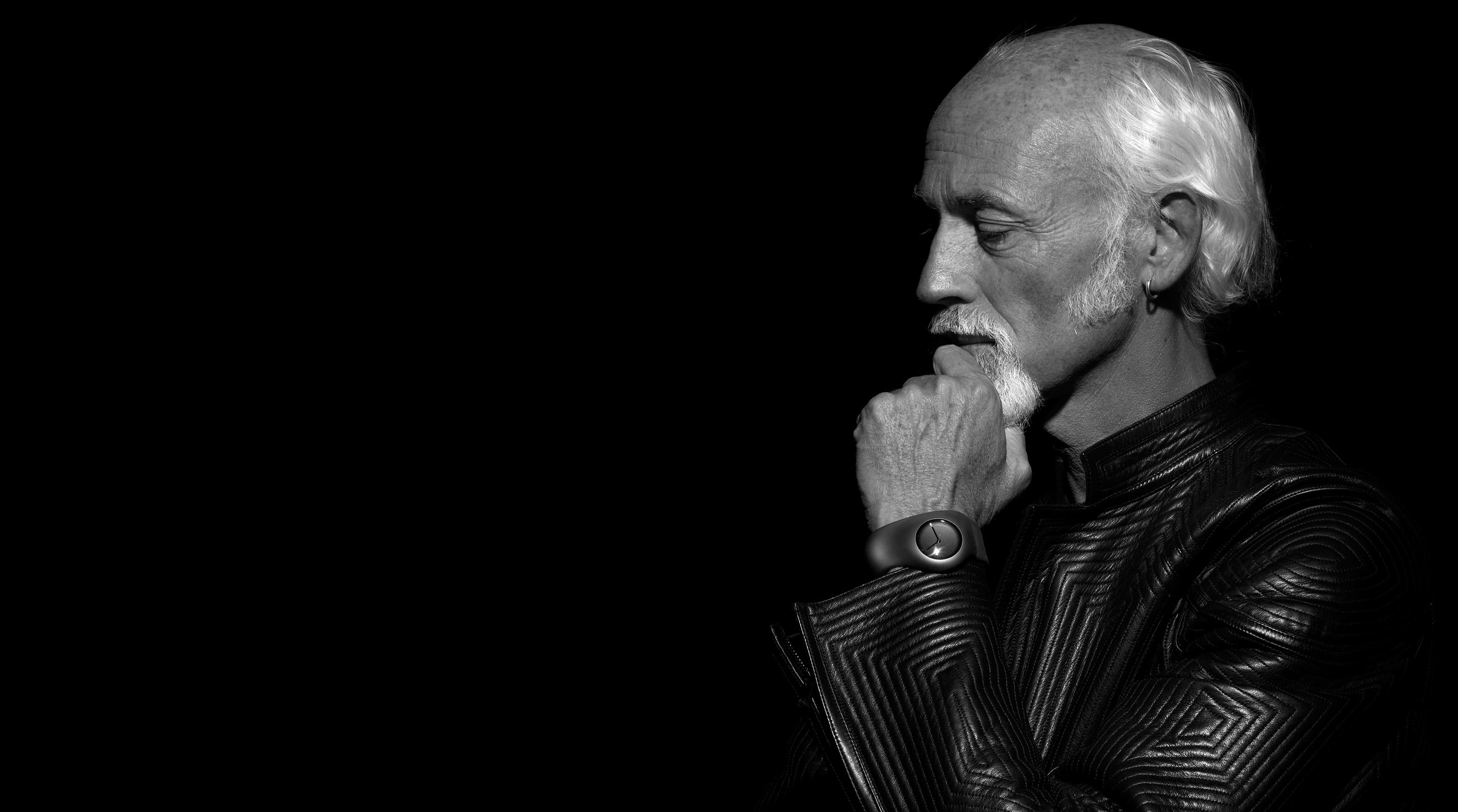

Ross Lovegrove is a visionary. Constantly pushing the boundaries of design and technology, he has won dozens of awards, has had solo exhibitions and is part of the permanent collections of major museums, and creates in seemingly every part of design, from architecture to objects to furniture to lighting. The consistent thread is a commitment and tenacity in experimentation. In his early years, he worked closely with Frog, then one of the leading industrial design firms in the world, helping develop products as iconic as the Sony Walkman and Apple’s first computers. He later went on to develop work for the leading design brands: Cappelini, Moroso, Artemide, LVMH, Vitra and countless others. Through technology and a deep connection to organic form, Lovegrove brings these seemingly disparate entities into an entirely new and innovative context, creating pieces that help define 21st century aesthetics. And he happens to be quite lovely as well. In this interview, we speak about his inspirations, the importance, and challenge, of staying true to yourself and how great design comes from many long moments of staring off into space.

Lovegrove:

Well because I never liked the word designer because it’s just so commercial and pigeonholed. And then I have such a … It’s such an effort to describe what you do to the common man. It’s really tough, ’cause they think it’s fashion or graphic or … Design has been hi-jacked I feel, in the last, certainly since I finished at the Royal College in the 80’s. It’s just become ubiquitous. Design is used as a word on anything from designer toothpaste to designer whatever. So when you talk about being creative, that gives you much more scope. It’s a release. It’s something you’ve got in you that you have to release. So if I met somebody and I said, “Oh, I’m an industrial designer,” I mean, I’d be slightly embarrassed actually. I shouldn’t, ’cause that’s the term, but it’s got such an archaic image that comes with it, an oily industrial image. And that’s why I’m interested in all the additive techniques and the 3-D printing and so on, because that is the future industry. And that industry is clean and efficient and ecological. So I’m much more aligned with that than I am with the old term. So I can’t walk around saying I’m a sculptor because people might not understand that either. So I’m a little bit lost. I can do all these things and you can tap me on the shoulder and I can design it, easy. Like breathing. But maybe that’s not challenging enough. Maybe there’s a new positioning. And it’s what you leave. It’s not what you do, it’s what you leave so that people understand maybe something that was missed. I don’t know.

“I can put a glass of water one side, and a glass of vodka or acid the other side, and what’s the difference?”

Arkitektura:

I know, I mean, what you leave, it’s … As you know, it’s 2:00 in the morning here, and I had actually, my studio is in Sausalito which is across the Golden Gate Bridge. And I’d forgotten my microphone at my studio. So tonight I drove to Sausalito, I live 40 minutes from Sausalito which is totally fine I love driving and I love driving across the bridge. And I was listening to, this is a long-winded way of telling you what you leave behind, but I was listening to this amazing podcast that’s out of San Quentin which is a jail here-

Lovegrove:

I know.

Arkitektura:

It’s extraordinary, it’s called Ear Hustle. And it was about being a father in jail. And about what you leave behind for your children by way of guidance and advice. And when you’re a maker of things, you think of what you leave behind in the context of an object or a building or … But when you’re not a maker, or when what you are might have a broader definition, what you leave behind can also be broader. And I’m wondering if, does what you leave behind, for you personally, does it lie in the object for sure?

Lovegrove:

Yeah. I mean, I think this free expression of how to release can go many ways. And for me, the great artists of our times, they are all that we can reference. People like, if you take Henry Moore, he could sculpt. Boy, could he sculpt. Gosh, could he draw. My goodness. And then if you read his writings, they’re so wise. I mean, they’re solid. They’re the son of a coal miner. They’re not Isamu Noguchi of Yone Noguchi. They’re not poetic. But you can’t argue with them because they’re just so solid and good to read.

Lovegrove:

And so it’s this thing about being the multifaceted. I find that really a measure of the true ability to release, if you think about it in these terms Tania. I was fascinated by, when I did this show at the Pompidou last year that was called Convergence because I was fascinated by that time in history when in the mid 1850’s where an archeologist would talk to a biologist who would talk to a physicist and they’d all meet and talk and share. At a time when you had to send letters, it was a very slow burn on how you would exchange ideas. But everything was being discovered, electricity was being discovered, all sorts of things were just … We didn’t even know what a faucet was or wasn’t. So there was a time when these people, the only way that they could communicate with others was through their writing or the ability to illustrate. So often these people were incredibly gifted drafts-people. I mean, don’t you find that fascinating, that they, out of that, was forced an amazing illustrative capability? Wow.

Lovegrove:

And yet today now it’s all softened up because we have other ways to visualize, which is quite fantastic, but that’s why I write and I draw. Because these are so private that in the future, maybe people will flick through them and think, “Oh what an incredible idea that was.” But I don’t have the energy, I certainly don’t have the time, I don’t have the resources to realize all these things that I think of and dream of, from autonomous vehicles to whatever. I can’t, ’cause I run a very small studio and I get what I get. So does that mean that I’m not allowed to express those ideas? So I do that privately, even … And I often think it’s better to have a really, really profound idea on paper than something irrelevant made.

Arkitektura:

Absolutely. I mean, your notebooks are your most treasured … Are they not your most treasured items?

Lovegrove:

Yeah, they are. It’s very funny actually, ’cause when the Pompidou wanted to display them they said … I went to Paris with them in a big aluminum suitcase. And they said, “Oh, leave them in the corner there.” I said, “Hang on a minute.” I said, “This is my life.” I said, “I’m not going to just leave them in the corner with the public coming through.” They said, “Okay.” So they took me downstairs into their storage and archives and I still wasn’t happy ’cause it just seemed a little bit lost. And the chap said, “Put them in the corner,” and I said, “No, I’m not going to just leave them in the corner there.” And the chap looked at me over his spectacles and he said in French [French] So basically, “Shut up.”

Arkitektura:

Yeah, exactly. [French]

Lovegrove:

[French] So you live and you learn. So although there are certain things you really have to be the guardian of. So that’s what I mean, there are certain things which are disposable, good or bad. But then the things which are deeply, deeply personal to you I think you just have to cherish. So yeah, so that will always be my main production, if you like, in my life. The other stuff just comes and goes. That’s probably why I haven’t done another book, because I need to do it myself. I need to know that the book is communicating something that’s non-commercial, that’s … I don’t know. That’s not just a promotion for me. What you show is where you go, so.

Arkitektura:

Yeah. It’s hard, it’s also, a book is a distillation of, I mean based on what it is that you would want to communicate, you really have to so deeply understand yourself and try and translate that. It’s …

Lovegrove:

Hm. Well I think that’s why things feel a little bit, a need for change, in a sense. To calm things down and to really understand. And I think, to have a sense of place with some new invigoration is a very important thing. There was a lovely thing recently on Frank Lloyd Wright, beautiful program. I only came in at the end and they were talking about during the Great Depression. I mean, he had no work at all at the age of 60. Zero. So they built Taliesin with his disciples, they all did that sort of for free, by hand of course. And then after three years he was given a commission to design a house. And six months later he still hadn’t even thought about it. And the client said, “I’m nearby, I’d like to drop in and see the design of my house.” So he sat down for one and a half hours to draw. And out of that came Fallingwater, which is probably regarded as the greatest house on Earth.

Arkitektura:

That’s amazing. It’s a great story.

Lovegrove:

Isn’t that amazing?

Arkitektura:

It’s an amazing story.

Lovegrove:

Isn’t that amazing?

Arkitektura:

That’s an amazing story.

Lovegrove:

And then of course you’ve got the Johnson Wax building, and instead of taking that easy, he did the roof of that in Pyrex glass tubes which even today I wouldn’t have a clue how to even approach. He pushed limits. And then at the age of 90, the Guggenheim. I mean talk about endurance. I mean that’s incredible, isn’t it. So I just … And he was Welsh by the way so that was a good one.

Arkitektura:

Is it true, he was Welsh too?

Lovegrove:

He was, yeah.

Arkitektura:

Really? Amazing.

Lovegrove:

He was. Yeah. Yeah, he was. So that was very encouraging, seeing that, because if you have these sort of dips and doubts of where you are, where you’re going, what … Tenaciousness or determination is quite important, to stick with something.

Arkitektura:

Absolutely.

Lovegrove:

And it’s not always about scale, that’s the thing. I don’t think it’s all about building skyscrapers and saying, “Look what I’ve done.” I think it’s quite the opposite. It’s a presence, I think it’s just having a presence really.

Arkitektura:

I think what I love about that story is just the, I mean there’s so many things, but that there are these creative, this sort of thing that lives inside you. And within an hour and a half you can just, if you’re in the right space or maybe you don’t even need to be in the right space, it has this sort of channel that comes out.

Lovegrove:

Well that’s the release I’m talking about. How can I say … Either you get immediate pressure to create, which you get a lot from China ’cause they don’t understand that you need to breathe and think. So they instantly, yeah, they instantly assume you can just kind of come out with these things. And with experimentation, you need to fail and go again, and that’s tiring. It’s very tiring, it’s very frustrating for the people who work for you. The digital realm that we’re in is very expensive. Because the people that you have to work with you have to be highly trained, highly skilled, educated. All the software, everything that goes with it, it’s suddenly a very different thing. And that’s why from time to time it’s important to work on something more craft-based or more immediate.

Lovegrove:

And when Frank Lloyd Wright was probably designing Fallingwater, he’s got the big piece of paper, he’s got the ruler, he’s got the pencil, and he’s a gifted draftsman who can draw with perspective and put the trees in and all those things. I mean, what an amazingly exciting ability that is. To out of nothing, on a piece of paper, to visualize three-dimensionally something which, a place he probably didn’t even have a photograph of given the lack of technology of the day. So it pushes it back more into the realms of a mind which is constantly being exercised. Which is not a lazy mind, it’s an exercised mind. So the moment that you’re given a situation to respond to, you don’t put a building away from a waterfall to look at the waterfall. You slam it straight on top and you don’t worry about humidity or noise or whatever, how you build it, nothing. You just go for the ultimate. And then you find a way to work it out. You don’t work below your potential.

Lovegrove:

And I try and work above my potential. One of the most I’m people I’ve met in my life, he used to say to me, an older man, he used to say, in Istanbul, he used to say, “Ross, you’re a master of what you don’t know.”

Arkitektura:

But how do you gain the … I think there’s a lot of fear around doing that.

Lovegrove:

Well there is because that’s a character thing. But it’s also a life thing. Because there’s a lot of pressures in life to live and pain and whatever you need to deal with in life. But I think if you’re truly creative, I mean like Rembrandt, he was destitute at one time. But he didn’t suddenly paint kittens, did he, just to sell paintings. So I think you stick with what you do, don’t you?

Arkitektura:

Yeah, I mean I think it’s, that’s why you’re a great designer. That’s why you’re one of the greats, because you’ve pushed yourself. And I think when you’re very good at something, it’s so easy to just continue to be very good at that thing. And to not push yourself, because it’s scary.

Lovegrove:

That’s so true. And you frustrate people, because you see things that they don’t see. Most people are quite, I wouldn’t say lazy, but especially if they’re working for somebody else that generally gets the glory, it’s very difficult to be servile on behalf of somebody else. So in my case, with the people around me, I try to maintain a position where I’m not lazy, I lead from the front, I take that responsibility. And then see where it will go. And there are lots of surprises in there, on route. But in a way, I’m partly looking to fill the gaps. Which means there are certain things I haven’t designed which I think, “Gosh, that would be interesting to do.” And then there are other things which are just contemporary responses to technological evolution.

Arkitektura:

Phaidon did that 10-year interview with you. And I mean, it was just like three questions. And I mean, I do like the Proust questionnaire, but I’m never a huge fan … Well, I don’t know. I’m not a huge fan of rote questions. But I did think that that was actually interesting. And what I found interesting about it was, there was this real excitement and energy with which you described your first studio.

Arkitektura:

-with which you described your first studio, or your early studio, which is so far from what you have now, because what you have now is so extraordinary. But in the way in which you worded it, it seemed like such an exciting time.

Arkitektura:

I’m just curious about that because creative people that are designers, artists, anyone in the creative field, or anyone in any field, of course, strives for success, and wealth, and recognition, and all those wonderful things that can happen. At the expense of sometimes forgetting about how great it was when you didn’t have those things, and I wanted to speak about the value of both.

Lovegrove:

Yeah. Well, that’s a difficult one because the past is the past, and Darwin never said, “Survival of the fittest.” He said, “Survival of those who adapt.” So if you don’t come from very much, and you’re outside of your realm, you feel different. You don’t know why, and you’ve got something to express, and you’re trying to find channels for that.

Lovegrove:

You will create anywhere. That’s why the notebooks are great because they travel with me. They’re non-site specific. They’re me-specific, if you know what I mean. So they have my body warmth, and what that has.

Lovegrove:

But I’ve become somebody that needs a studio, meaning if you came in even without me, you would feel like you met me. That is very, very important for me. But the objects around me are things which are not only self referential, and keep me on the straight and narrow in terms of my own contribution … So I get reminded of my not only positioning, but my thoughts on how I design. That’s important. And I’m regularly building objects and things which I don’t need.

Arkitektura:

Yes, I love that.

Lovegrove:

I just do it because I just need to have those things around me. That’s what I’ve spent my money on. Some things were delivered yesterday that blew my mind.

Lovegrove:

So I need that space. Not only for myself, but it has my DNA in it, and if anybody comes, they go, “Oh, my God.” It’s a little bit like going to Brancusi’s studio or something, and you just feel the presence, and I think that’s really important.

Lovegrove:

But I could do that kind of anywhere, and I am kind of in the mood to recreate that somewhere where I can also have an indoor/outdoor experience. I can live with it more within my world, so that’s-

Arkitektura:

Your internal world.

Lovegrove:

That’s important. But I think that’s important for all them Constantine [Gritchard 00:37:10], all these different designers. I think, for me, they’re interesting because they come out of the Atelier system that was the great Italian system. You know, the Castelleones, and so on, that had really interesting studios with very interesting artifacts and objects. And we’re not just a sort of digital internet group of people. That we’re physical. I’m physical, so actual reality. I’m into that. I’m interested touching, tactility, presence. ‘Cause I create objects basically.

Arkitektura:

Yeah, it’s very interesting. I love Brancusi’s studio at Centre Pompidou, and it’s very telling what people surround themselves by in their creative spaces. You know, there’s … I don’t know. I think Monocle, or maybe the New York Times, I don’t remember who does it, but they go into a designer artist’s studio … What’s the significance of these things?

Arkitektura:

And remember when I got my desk. It was massive. It was the biggest desk I’ve had, and I’ve immediately covered it with rocks from Stinson Beach, and poetry, and little things that I’ve gotten. New plants, and all these things that inspire me, and that really define who I am. That my way of saying, okay, if you come into this space, you can look at this table, and then you’ll get a real sense of who I am without me telling you. And we need that. We need that.

Arkitektura:

You were saying earlier that you don’t use Instagram, or Facebook, even though your work is at Facebook. And Facebook is … And all social media is this myth of how technology makes us more human and more connected, which in some way it does. But in others, it doesn’t.

Arkitektura:

And when you say humanizing technology, what does that mean?

Lovegrove:

Well, that means it’s on your terms again. I think it can be in the physicality of the object, without getting too kind of romantic about that, but I think it can be something in the object which makes the presence of that thing more …

Lovegrove:

For example, you take a desk light. That desk light is probably, at home, is off for almost 20 hours of its existence, so why is it screaming light at you? Why can’t it just be off? Be an enclosed object? There’s different ways intellectually to look at things, so that might be a way of humanizing.

Lovegrove:

But you touch upon social media, and it’s about surveillance, and all these objects now that would be great to have something that you can ask questions to at home, and it would help your life. But without feeling like you’re under surveillance, and that they’re selling information on to advertise things to you, to create more consumption. Some of these things are really wonderful, but they go too far, and there’s a lack of trust in things. I can show you a gold watch in one hand and a gold watch in the other hand, and one could be real, and the other one’s fake. You don’t know the difference. I can put a glass of water one side, and a glass of vodka or acid the other side, and what’s the difference?

Lovegrove:

So it’s this return to an instinctive position without having the instinct burnt out of you that you become so codependent through this new channeling that you sort of give up. So you’ve got to stay raw in a Tony Cragg, in a Kapoor, in a Henry Moore kind of way. You run at a block of clay and punch it, so you stay present.

Arkitektura:

Not always easy to do. Certainly the goal. It’s certainly the goal.

Arkitektura:

So the term “organic” is always … It’s just like, “Phhh.” Organic work is very organic designer. The fluidity of the objects is so organic. I wondered how you felt about that term. Does it resonate?

Lovegrove:

Yeah. We’re lacking a number of terms. You can say anthropomorphic, almost something biological. Everything has a kind of meaning, but “organic,” the term has been taken over by nutrition more than form. I think it’s too nebulous, I think it’s too simplistic. I think often when people in the field, who are interested in design, they confuse designers. They confuse something which is blobby and very, very poor, reflexive geometries that just are painful with things which are really deep and thoughtful, and evolved.

Lovegrove:

So if you take natural elements, by definition, they’re not designed, are they? They grow and they respond to atmospheric condition, or whatever that is. And they assume forms which are so fascinating. They’re either fashioned over time, or fashioned through growth. So the direct link is with a natural force, and nature, I think, is a force like gravity itself. So we need to understand … You need a popularization, otherwise nobody’s going to understand it.

Lovegrove:

But I’m talking more these days about universal consciousness rather than popular culture. So that’s more where I’m at, but I think the world shares a universal consciousness of natural forms. So if you want to talk about this commercially, or whatever, you could say that you don’t need languages. It’s a universal condition that the whole world would understand because everybody loves beautifully considered and thoughtful form in unison with the right material. So that’s anything from a wonderful [inaudible] of some chair the way through to even something that Space-X is doing. Just well considered form with the right material and technology.

Lovegrove:

It hasn’t really been written about, or talked about and defined the way that organic form relates to emotion, which relates to anthropological ideas, to evolution, expression. I mean certainly we relate, I think, organic form to the evolution of sculptural pieces. You can see it in design, too, but so few people have really defined what I think is really true, sophisticated, organic design. That’s what makes it rare. But, you know, I like rare things, but rare things tend to go against the grain of what I’m supposed to say as a designer saying, “Look, you’re going to sell zillions of these things” when I hope they don’t.

Arkitektura:

Because in the end, that doesn’t completely satisfy.

Lovegrove:

Well, it’s not my motivation. I think there should be a natural supply and demand. I’ve always talked about how much I dislike artificially induced consumerism. So this high level of deception of drawing somebody in to buy something. Once you’ve bought something, it’s almost impossible to get rid of it. There’s not systems in place.

Lovegrove:

So, I don’t know, I might sound a bit odd, but I’m not impressed by the numbers. It seems to be the way of our world right now, but …

Arkitektura:

But you’ve been extremely successful.

Lovegrove:

Yeah, with some kind of resistance. Well, because I’m true to self, I think. I can’t fully answer that, but I think it’s because I’m really true to self, and I’m true with the people I have to talk to, companies, about why we do things. You could do one amazing thing, and that could be the equivalent to a life’s work if it has meaning.

Lovegrove:

I said to somebody the other day … I said to [Gosh], “If I had to meet David Attenborough, and he asked me what I did for a living, and I didn’t want him to walk away, what would I have to say to him?” Because you’re not going to say to him, “I did a lovely range of cosmetics.” He’s going to just walk away. So it’s how you … What do you say to people that you feel that you’ve got some integrity, and whatever?

Arkitektura:

Did you come to an answer? What would you say?

Lovegrove:

I don’t know, but I went to the Galapagos a couple of years ago with Richard Dawkins, the great atheist. From time to time, I’ll draw around interesting people’s hands in my books, because they sort of fit the book. People I might meet or encounter. So I wanted his hands. So I asked him, and it’s a kind of peculiar request, a mature man saying, “Look, could I do this?” He was reluctant, but I did it, and it gives you enough time to study. And you can see so much through people’s hands, it’s incredible.

Lovegrove:

So you do that. And then I said, “Look, would you mind if you could just write something, or whatever. Sign it, or whatever. So he wrote next to his hands one of the greatest things I’ve ever heard in my whole life, and it’s probably one of the greatest statements ever for humanity. He wrote, “Life on a planet comes of age when it first works out the reasons for its own existence.”

Arkitektura:

That is beautiful.

Lovegrove:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Lovegrove:

But we should all live by that. Forget the rest. You know, it’s just how you move through life. I’m just trying to calm it down in a way to see how far I can push this. Design is borne like spraying a mist in the air to reveal what is naturally there.

Lovegrove:

My staircase does that in my studio, for example. I mean, these things which I didn’t know why I was doing them at the time, but now, as I get older, they all fit into place in a sense. The economics. The lean, efficient, fat free way of looking at things. That’s been in it since I was young.

Lovegrove:

So I can move between ecology and those kind of projects. Talking to people in Dubai right now about doing a new solar tree. I was doing that yesterday. You know, so I engage with that. I engage with the world of sculpture and art, and I engage with innovation, but I also engage with nothing, meaning I can walk away. I can walk into the sunset with my notebook and think, because that is a contribution, too.

Arkitektura:

Absolutely. Potentially the best one.

Lovegrove:

Yeah. I think.

Lovegrove:

My father always said to me, “You do what you do, son,” which is almost no advice, but it’s actually quite lovely. No pressure.

Arkitektura:

That’s beautiful advice. Okay.

Lovegrove:

All right.

Arkitektura:

Take care.